Preparing hives for Spring

/I've been inspecting hives in this gorgeous weather and wanted to share a few observations and methods for spring.

Photo of Jennifer by caley morrison

Plums have started to bloom in most locations, providing a good source of early nectar. Eucalyptus has been blooming for a while now in most locations, also a great source of nectar. Willows and acacias are blooming, a good source of pollen. Maples and other hardwoods will soon be blooming, along with early fruit trees such as apricots, cherries and almonds.

Bee gathering acacia pollen

Most of the hives that were in good shape going into winter are starting to increase brood production and need room. By good shape I mean they had one or more full boxes with drawn comb and resources, were treated for mites in October/November. To those hives I've been adding boxes of drawn comb to the bottom of the hive stack- this method is called Nadiring, (opposite of Supering) and allows the bees to move down as the hive grows. This method is best for nights when the temperatures are still on the cool side, since the bees won't have to move up to stay warm and can still access resources around them. Nadiring is also a great way to add new boxes of undrawn comb to your hives. You should only add new, undrawn comb during a nectar flow, but now is a great time and will give you a leg up during the swarm season.

I'm seeing a few hives with swarm cells, but I don't yet consider it to be swarm season. These are hives that overwintered in a single brood box and are growing, so they are really crowded. Why don't I consider that an indication of swarming? Because a swarm from boxes this small would risk both the parent and the daughter colony, because neither are big enough to fare well this time of year. Hives exhibiting this behaviour need to be given more comb to grow, and this will usually get them to relax and stay put for a while longer.

Signs of good nutrition, with brood surrounded by fresh pollen and nectar

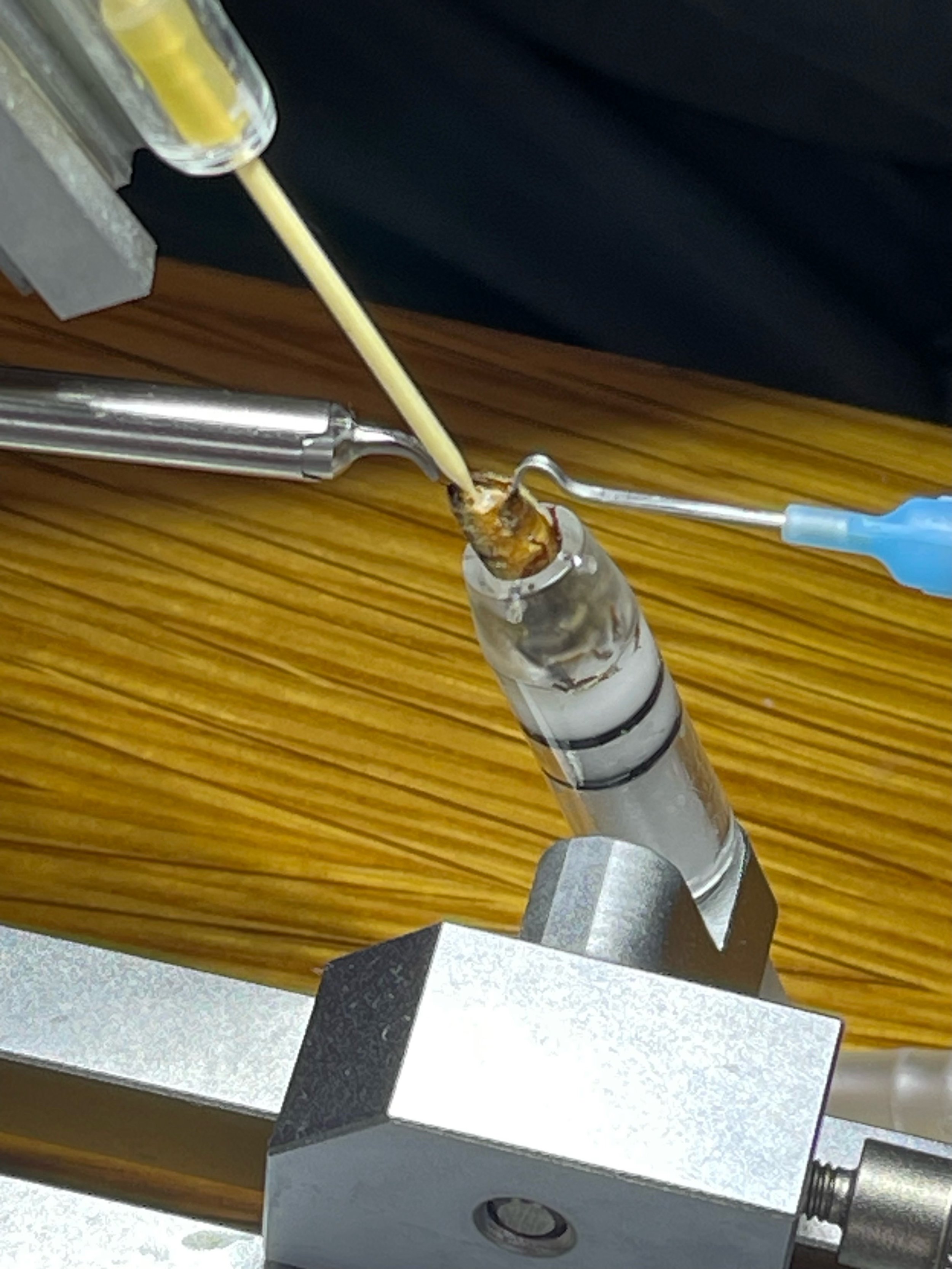

Some of the hives have needed resources. If you open a hive and there is no fresh nectar and pollen in an arch surrounding the brood, they are suffering from starvation and malnourishment. It's getting warm enough in the daytime to feed syrup again. I use a mason jar with holes poked in it over the hole in the inner cover for fast delivery of food.

my favorite way to feed syrup

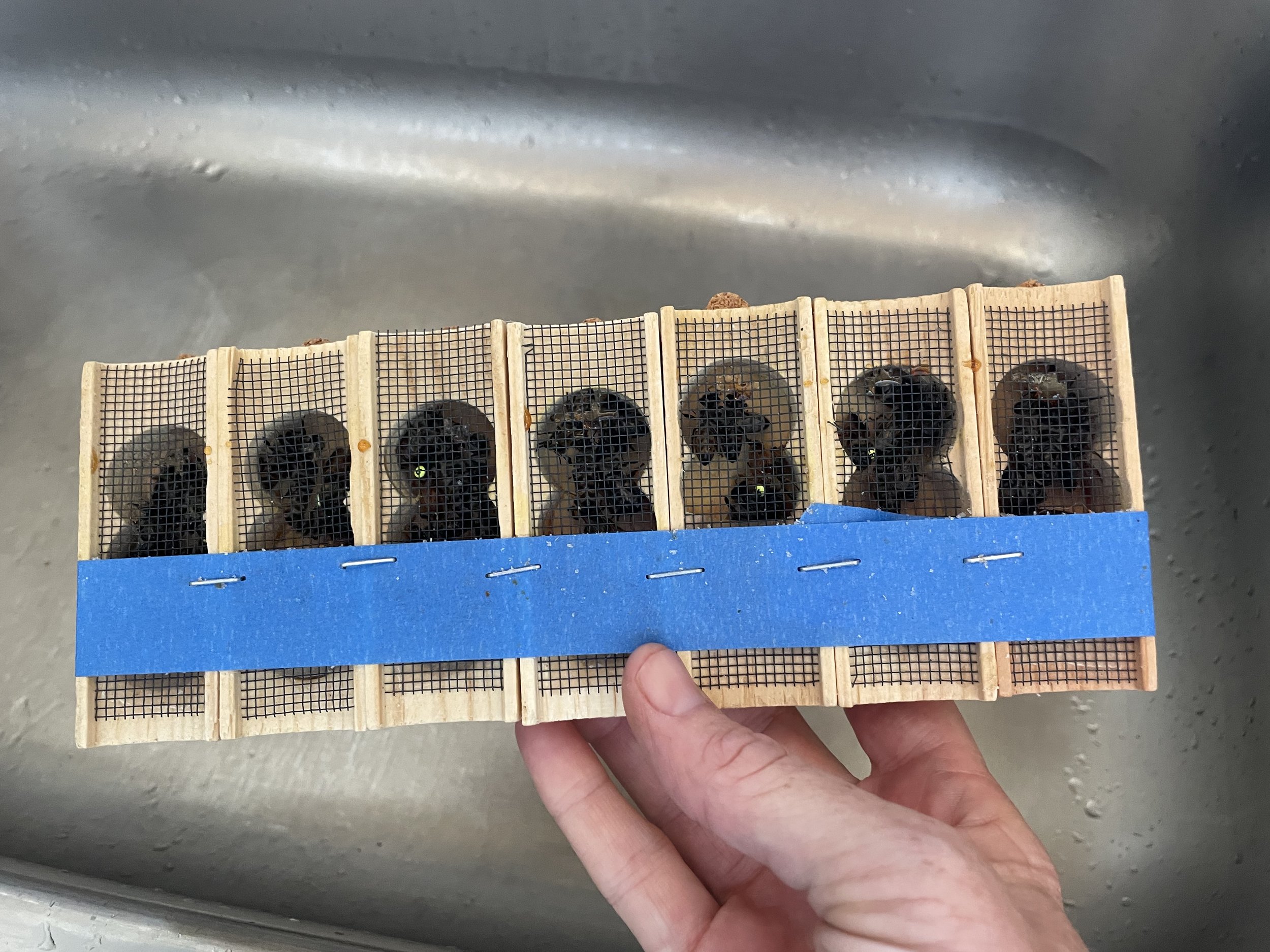

I'm also seeing hives with Deformed Wing Virus and chewed brood, a sure sign of mites. This is the case especially in the larger colonies. Why so bad this year? Because it was so warm this winter, many hives never stopped raising brood, and mites reproduce in bee brood. Pay close attention for hives exhibiting hygienic behavior, the most common indication is being able to see the tiny white faces of bee pupae looking out at you from inside the capped cells. The leading theory behind this behaviour is that some bees smell varroa and will uncap those infected pupae, thus reducing moisture and preventing the mites from reproducing but not harming the pupae inside.

“bald Brood” is an indication of mites and hygienic behaviour

It's a good time to plan your mite treatments now. Once, a long time ago when varroa and its associated pathogens weren't as bad as they have become today, we wouldn't necessarily worry so much about varroa treatments. The idea was that the hives would outgrow varroa in the spring. But with the prevalence of viruses like Deformed Wing Virus (with 3 known strains!) it has become more difficult for sick hives to recover from a high mite load when their populations are low. There are more than 20 known viruses that benefit and are spread by varroa, and they continue to evolve at a rapid rate.

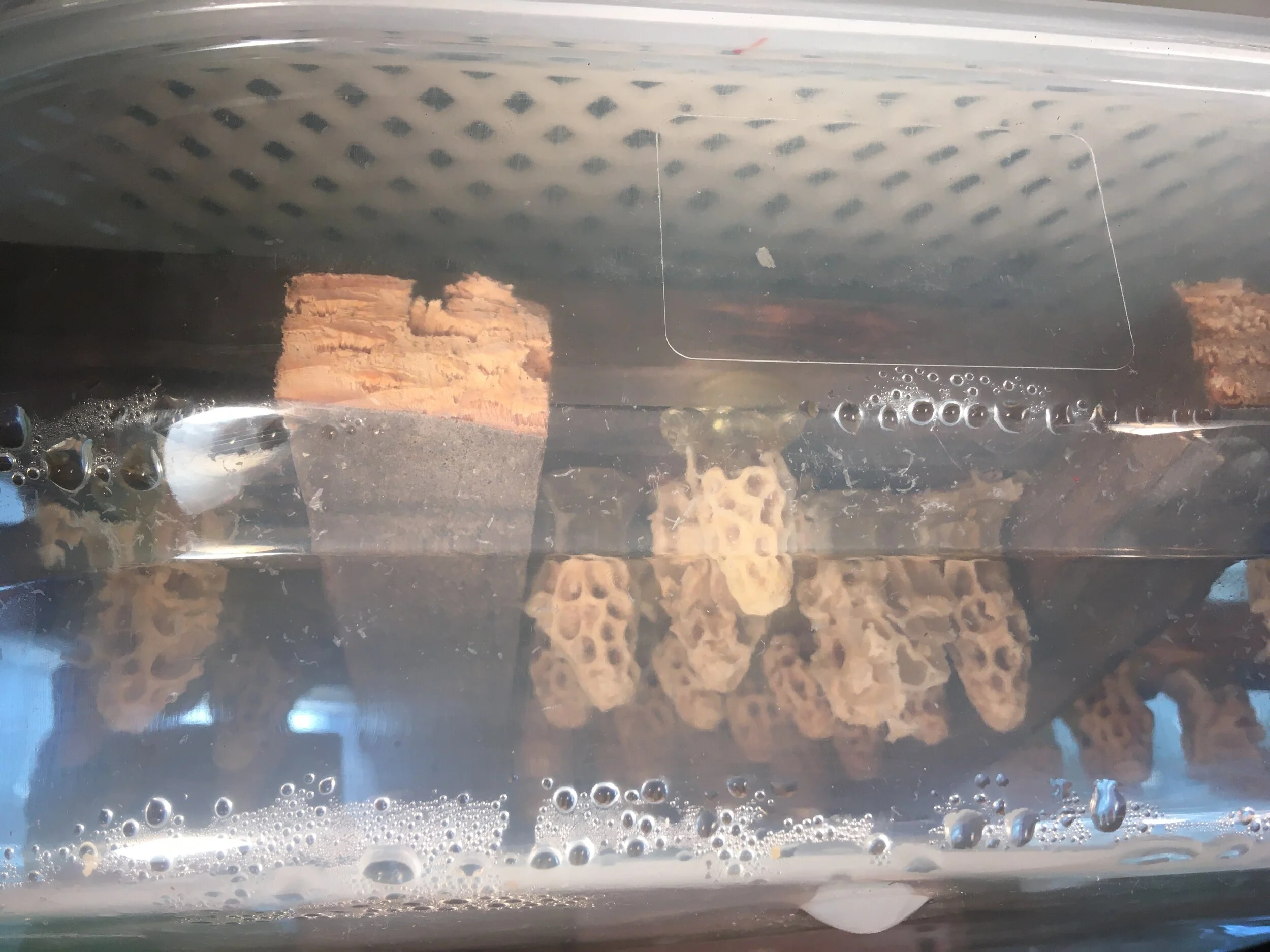

Healthy, well-fed frame of capped brood.

On a side note:

I had a few hives that were queenless or broodless when I opened them, but winter bees live a long time and their populations are often quite stable. Those hives get a frame full of eggs, larvae and nurse bees donated from a strong colony. If the colony is strong enough, they can produce queens from 1-day old larvae. It's a bit early for queens to mate successfully, but if the weather holds steady the hives might have a shot at recovering. It is for this reason that I always double up on my hives, so that one can borrow eggs from the other when it is queenless. The same works for resources.